Phantom of the Paradise

(1974, Brian De Palma; Shout! Factory disk)

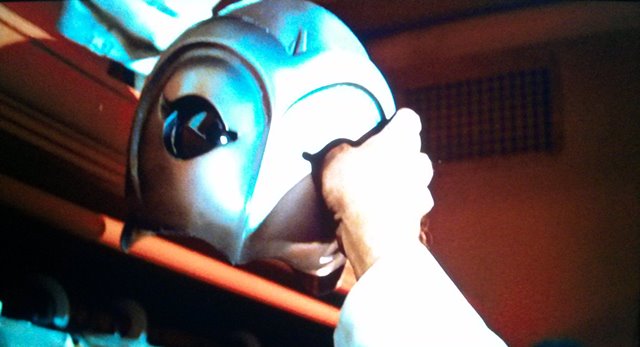

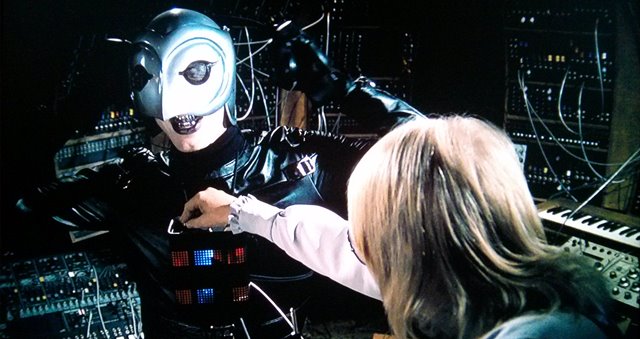

Phantom’s ambitious story combines several classic psychological horror plots: in addition to the Gaston Leroux serial from 1909-1910 in which a deformed and frustrated artist haunts the venue where he was ruined, lusting after the pure woman who is his last connection to humanity, the movie also loops in the Faust story and Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Williams makes for a singularly seductive Mephistopheles, from his purring voice to his affected dress; he’s smartly cast to set his diminutive size and seeming harmlessness against his all-powerful, all-seeing evil; his henchman played by George Memmoli is huge in contrast to Williams. William Finley as (first) the hapless and goofy songwriter taken advantage of by Williams, and (later) as the mangled and tortured monster again bested by Williams, is beautiful to watch, with so much of his performance in his carriage and the one visible eye through his mask; in one nicely underplayed gag, all of the door frames in both Williams’s mansion and studio are 5” 6’ to accommodate him, forcing Finley to grotesquely contort his body to get through them. The ingenue and Finley’s obsession is played by Jessica Harper, who projects wholesomeness and likability even as she proves to be just as ambitious as both Finley and Williams. Finally, four key musical frontmen play the contract employees of Williams’s conglomerate who are tasked with delivering his music to the masses, packaged and repackaged to fit the latest trend: Archie Hahn, Jeffery Comanor, and Peter Elbling front doo-wop band The Juicy Fruits, surfer band The Beach Bums, and shock-rockers The Undeads in turn, with Gerrit Graham added to the final band as the lead singer intended to carry the Faust role written by Finley (and which he’d intended for Harper). The changing bands, cynically sold as the next hot thing, are a powerful conceit, explicitly accusing mass media and mass entertainment in the grinding down of art and artists, while implicitly criticizing the (teenage?) audience that drives the evil empire with their undiscerning consumption. (There’s some suspicion in the documentary material on this disk that this theme wasn’t understood by the distribution people at Fox, who tried to sell the movie to the same teens that were being satirized, with mixed results.)

The De Palma hallmarks are all there — fully developed, in a surprisingly early entry in his oeuvre. It has his Hitchcock homage, an attack in a shower a la Psycho. It has his split-screen, here serving a truly tense scene: two angles on the same band rehearsal allow unsuspecting dancers and musicians to run into a time bomb that’s been planted in a rolling prop car, with the cameras following each as the car comes closer and closer together and eventually (after several minutes, during which the bomb’s ticking is heard throughout) reaches them just at the moment of mayhem. Another De Palma specialty is shown off in the long final scene, the Williams-Harper wedding sequence. Using the experience he’d gained with documentary-style continuous shooting for Dionysus in ’69, De Palma put all of the cameramen in costume as members of William’s ubiquitous press photographers. De Palma’s choreographers-cum-crowd-wranglers were tasked with organizing the scene’s overall action: the primary actors had lines, blocking, and marks to hit; other actors had specific bits of business they had to fit in; the remaining extras mostly had to stay out of the way. Then the entire sequence was filmed in one go, with everything taking place in real time pretty much as it does in the final film. De Palma had to trust that he would have enough varied footage to cut together to tell his story; the end result (reportedly from only two takes) feels “real” in a sort of hyped-up, media-exaggerated way — furthering the overall theme of corporations manufacturing and selling packaged, inartistic experiences.

Reminds me of:

Rocky Horror, obviously . . . . I love The Rocky Horror Picture Show as much as the next seventies kids, but Phantom has far more going on than Richard O’Brien’s goof on RKO B-pictures ever did. Rocky gets its shocks (and, frankly, most of its value) from transgression and its twisted one-to-one cooption of each beat from square, classic horror movies; that’s made clear from its first scene (listing the science fiction and horror films it will cite) to last (where the RKO logo is literally the portal back to the alien world). There’s no real social satire in Rocky beyond its minimal critique of the “straight world” suburbia of Denton contrasted with the freaks and the freak nature that apparently exists in everyone. The joys of Rocky really surface when the movie is beside-the-point, just a canvas for a communal experience where theatergoers yell and dance and throw things at the screen. Phantom, in contrast, actually rewards close watching; like all De Palma films, it’s a beautiful object which opens up to reveal hidden themes and ideas.Of course both Rocky and Phantom have great music. Williams’s songs and score are just perfect; it’s a bonus that several of the numbers are intended to mimic and poke fun at certain popular rock styles to be sung by the three iterations of Swan Enterprises' house musicians reconstituted as 1950’s greasers, 1960’s surf dudes, and 1970’s shock rockers (like Alice Cooper). Every time Williams composed for the the screen, he turned out exceptional work: The Muppet Movie, the “intentionally bad” songs for the songwriters in Ishtar, Bugsy Malone (which has subsequently been turned into a stage musical), A Star is Born. I wish he’d been given as many chances over the years to score films as the (admittedly also awesome) Randy Newman. (Interestingly, given this movie’s plot point of a composer creating “the first rock version of ‘Faust,’” Newman wrote his own (not very successful) Faust in the mid-1990’s; I have the concept album.)

The sequence of the bomb being placed in a prop car trunk is a clear echo of Welles’s famous opening shot for Touch of Evil, where the camera follows a bomb-laden car through a border crossing in continuous real-time; the double-framing is almost a one-upmanship in terms of technical prowess. It’s not as beautiful as some of his other split-screen work (I’m very partial to images in Blow Out) but it is chillingly functional. I’m sure De Palma put in a zillion more directorial homages beyond Hitchcock and Welles; I’m too dense to find them, but I’ll say (betraying my personal obsessions again) that the ever-present cameras and Williams’s console of spying video screens reminds me of Dr. Mabuse in general and specifically of my favorite, Lang’s The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse.

But then — the guilt!

This movie has plenty of recognizable character actors and repeat De Palma performers, but I was particularly bothered by Archie Hahn, one of the three contract musicians and the lead singer of the first number, the Juicy Fruits’ “Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye” — he felt so familiar to me, like an old friend you recognize at a party and just can’t place. I looked at his long credits list in IMDb for a while before it came to me: He has that literally-five-seconds-long role in This is Spinal Tap as the hotel employee delivering room service to the band, with the absolutely perfect line delivery: “Thank God! Civilization!!”

Watching Paul Williams’s performance and listening to his songs, and then seeing him on this disk’s extras (in particular a long interview conducted by his friend, director Guillermo Del Toro) reminded me yet again of the apparently superlative 2011 documentary about Williams’s career and fight with drug addiction, Paul Williams Still Alive. It’s on my neverending list of films to see, and now it bumps up a notch or two.

Actor William Finley thinks that the Phantom costume he helped design — full-head mask, black leather body, cape — was ripped off for Darth Vader in Star Wars VI: A New Hope, specifically the blue-and-red light-up pushbuttons on the chest. This is in the BTTG section and not the RMO section because, full admission: I would never have noticed this.

Pitch:

I think that you are either grabbed by the very first moments — the Juicy Fruits singing their 1950’s pastiche — or you aren’t. All of the show’s humor and appeal is right there. Or if you’re more of an old-school horror aficionado, the sequence where Finley is transformed into the monster is perfect — genuinely disturbing yet still funny and a clear connection to the horror films of the past.

* Pencils down for me: Now that I’m done writing this #WTW (and you, theoretically, are done reading it), it’s time to really dig deep into Phantom of the Paradise by exploring every corner of The Swan Archives. This tribute site is one of the best I’ve ever seen on the web — beautifully written and designed — and while it helped me avoid some obvious mistakes here, I promised myself that I wouldn’t indulge in their scene-by-scene visual analysis, their extensive production and release history, or their long list of artifacts and collectibles until after I’d posted my own hastily considered points, lest I outright steal their work. They carried the torch for Phantom for such a long time — becoming the official owners of the film’s outtakes and other cut scenes — that when it came time for Arrow Films and Shout! Factory to create these definitive editions in 2014, it was this site (the “Principal Archivist”) who provided all these extras to the two companies. It’s a master class in how fandom should work. Please go there now!