(Cries of faint praise! here's #WhatThomWatched #20)

The Day the Earth Stood Still

(1951, Robert Wise; Fox disk)

For genre- and old-movie fans, The Day the Earth Stood Still is an unassailable 1950’s landmark; for millennials, one imagines that it’s almost completely unknown (despite a bombed 2008 update with — whoa — Keanu Reeves as Klaatu). And then for some of us gen-xers, too young to have seen it anywhere other than on the UHF late show, it’s mostly remembered as the lead-off to the Rocky Horror Picture Show; in its three opening lines, “Science Fiction Double Feature” and those disembodied lips neatly summarize the entire plot: “Michael Rennie was ill . . . . but he told us where we stand.” (Well, “Michael Rennie was shot accidentally by a nervous United States serviceman as a metaphor for the state of anxiety and paranoia that gripped the world during the Cold War” might have been more accurate, but it wouldn’t have scanned.)

Yes, this is the one where a seamless space saucer plunks down on a ballpark near the White House and a placid, affable, well-spoken alien comes out, accompanied by an all-powerful bodyguard, the robot Gort. They have a message for mankind, in response to its recent unlocking of atomic power. Washington’s finest play it cool and don’t overreact much — it’s just one bullet that puts alien Klaatu in Walter Reade hospital when he tries to pull the hostess gift he brought for Earth out of his pocket. (He’s fine, of course; he walks out of his room to try and find someone more reasonable to talk to, and eventually hooks up with Earth’s most famous scientist, the Einstein stand-in Professor Barnhardt.)

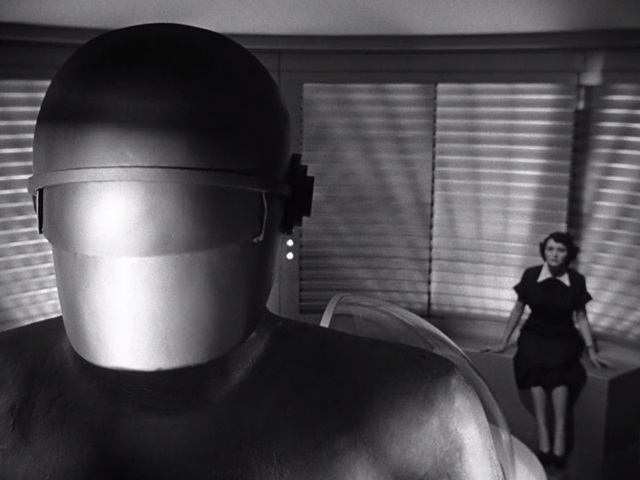

Day stands as perhaps the most famous example of high-minded, socially conscious science fiction of the 1950s. Along with the pure pulp, dimestore-rack thrills of Not of This Earth or It Conquered the World (and many others) came several of these films — When Worlds Collide, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and the superb Forbidden Planet among them — but Day was one of the first. It’s also lovely, with gorgeous technical work and seamless special effects, truly exemplary of the time, and with a historic double-theremin soundtrack by Bernard Herrmann. It gets many details right, whether by design or chance; the unknown-in-the-States Rennie creates an alien with an aloof dignity which wouldn’t have worked with a bigger star; it’s hard to imagine Spencer Tracy working in the role, for instance, as great an actor as he was. He’s just too recognizable. Similarly, the metal behemoth Gort is as smooth and impenetrable as the spaceship; other than a before-the-fact resemblance to the 1970’s Battlestar Galactica Cylons with the visor and red light/death ray, it’s completely unknown and its motives are unreadable.

But, still . . . . there are tropes. Maybe inevitably so; it’s a source of the tropes, after all. It’s the classic aliens-as-guardians-of-the-universe story, with an edge of menace — get it right, Earth, or you’ll be sorry. There’s a curious little boy who befriends the alien and figures out the truth before anyone else; there’s the protective mother who ends up protecting the mission; there’s a scientist as an ally against the fearful man on the street. The actual beats must have been recognizable even in 1951, especially to the core audience of Astounding Stories pulp readers: emissary from the stars, triggered by our development of the bomb; a perfect, implacable weapon-slash-protector-slash-healer (really, is there anything Gort can’t do? it’s probably also the perfect can opener a la Padgett’s “The Proud Robot.”*) And yet — the military/government is well-meaning (it’s a jealous man mistaking Klaatu for a romantic rival who causes the trouble; weapons and fighting are taken off the table quickly (even a fatal gunshot is, in the end, harmless). The “demonstration of power to the entire world” concept is standard but the non-lethal form it takes here is not. For a movie with a flying saucer and a giant tank-splodin’ robot, there’s a notable lack of luridness.

And there’s no suspense for viewers in that we know Klaatu is a good person; the tension only centers on whether or not he can complete his mission in time by keeping his few allies on his side. What must his home civilization be like, based on the sparse clues in the film? He sees no point in joining in the boarding house residents’ card game (he just stops short of saying “We don’t play games”), and he’s amused by a music box (implying again that it’s pointless). He’s more interested in little Bobby, seeming to sense that the child’s natural curiosity is a better fit for his message of non-aggression than any of the adults. The implication is that the extraterrestrials aren’t much different than us but have solved several inevitable societal issues: their bodies are similar, but advances in medicine including eliminating cancer have extended their lifespan**; they apparently have our same warlike tendency but their automated justice system tamps it down (as with Padgett’s “Two-Handed Engine.”*) They don’t seem to be welcoming Earth into an interplanetary treaty of some kind — it’s not as if they will continue to gift their technology and advances beyond some tokens. Their mastery of power/electricity/endothermic reactions would indicate that they could solve all of Earth’s power issues wholesale. A “use of power” anxiety in the 1950’s is the U.S. version of a Godzilla movie for Japan; both are reactions to the bomb. An alien force which explicitly nullifies weapons (guns and tanks vanish, but the power shutdown would indicate the ability to stop a bomb blast too) specifically forces the United States to consider what its foreign powers and policies would be in the absence of sticks — would our carrots alone be enough to “lead the world”?

Reminds me of:

Lots of movies recall shots in Day. Time Bandits similarly opens with a series of dissolves from deep space into Earth (and Gilliam’s film reverses this at its end). Montages of the general populace listening to radio news broadcasts are reminiscent of any number of films, most recently for me Thieves Like Us — though there are clever innovations of this here, as when Rennie walks alone on deserted streets and the sound is completely given over to the broadcast as he sees person after person listening to radios through various windows. There are television news montages as well; the use of playback monitors in shots with broadcasters again mirrors many films, with Manchurian Candidate coming to mind. Klaatu helps Professor Barnhardt with the math problem left on his blackboard — is this a common wish-fulfillment dream for a would-be intellectual, as in the opening scene of Rushmore?

The very simple and effective double-exposure techniques remind me of Jean Cocteau’s work from just before, in La belle et la bête or Orphée. Director Wise himself used equally beautiful and simple effects in The Haunting a couple years later, creating utter dread with a simple reversed black/white shot; here, tracking light points and light burns create spaceships and nullify weapons. The Gort effects work in a similar way; the idea of solid metal flexing fluidly like rubber seems pretty obvious now (it is made of rubber) but must have been uncanny then — I’m reminded of Padgett’s “The Twonky”* where the lead’s new hi-fi console unexpectedly starts walking around the apartment on its plastic legs, which suddenly can bend and flex.

I also liked the simple circular design of Klaatu’s ship, and the computer interface which is both gestural and voice-based — shades of the Doctor’s TARDIS interior. Speaking of the ship, the pivotal Gort/Klaatu scene reverses the “mad scientist animates corpse/robot/monster on a slab” trope from Frankenstein, Metropolis, The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the like, with the “monster” reviving the “doctor/scientist” figure. In many ways, that reversal encapsulates the entire film’s approach — it’s a kind of anti-horror film.

But then — the guilt!

There are so, so, so many classics of science fiction that I’ve never seen: When Worlds Collide. Destination Moon. Conquest of Space. DVD Savant fave Invaders from Mars. I could take a year and just focus on these and others from the 1950’s and 1960’s.

I don’t particularly feel guilty about skipping the Keanu remake.

Pitch:

The actors aren’t really in Washington D.C., but there’s plenty of great second-unit location shooting and rear-projection that puts the actors on my home turf. Bobby and Klaatu’s visit to the Lincoln Memorial is one of my favorite scenes — surely we are expected to compare the giant stone Lincoln to Klaatu’s Gort — another kind of peacekeeper? “These are great words,” Klaatu comments as he reads the Gettysburg Address. “He must have been a great man.”

* Lewis Padgett is a pseudonym for the unbelievably great husband-and-wife science fiction team of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore, who published from 1941 until Kuttner’s death in 1958. I adore the stories mentioned and many, many more. I could have shoehorned in an allusion to “Mimsy Were the Borogoves” too, but I didn’t want to push it. All these stories are in The Best of Henry Kuttner — the same edition I loved almost 40 years ago is out of print in hardcover but it’s currently on Kindle for three bucks.

** I don’t usually wink at unintentional ironies in otherwise great movies, but the scene where the doctors discuss Klaatu’s health — they think he’s 35, but he’s 70 with a life expectancy of 130 — is funny; just as the one is saying “So how does he explain that?” they are both lighting cigarettes.