Seven Chances

(1925, Buster Keaton; from The Art of Buster Keaton box set, Kino)

The plot is pretty ridiculous, but Keaton’s light touch keeps it just on the right side of plausible. His character has a perfect girlfriend (Ruth Dwyer), on whom he dotes but to whom he repeatedly fails to commit. On the morning of his 27th birthday, as he and his business partner are agonizing in their office over a ruinously expensive legal issue, he’s pursued by a man who he thinks is a process server but who turns out to be the executor of his grandfather’s estate: Keaton’s business troubles are over, because he’s inheriting a fortune, seven million dollars. As long as he’s married. By 7:00 PM — on his 27th birthday, of course.

No problem — he’s got Dwyer on his line, just waiting for him to reel her in! But in a scene that is far better than the usual rom-com “misunderstanding that puts the couple at odds,” she’s turned off by his newfound urgency — or in his words, he’ll inherit the money “provided I marry some girl today” . . . oops. Despondent at the loss of his true love, he trudges back to his partner and his attorney, who then have one mission for the rest of the film: get Keaton hitched at any cost. The romance is built in to the fact that we know Keaton and Dwyer are still in love; we don’t have to see any further interaction between them. Keaton’s emotionless demeanor tells us here exactly how unenthusiastic he is at each opportunity, starting with the first set of women — all seven women that he knows at his country club and therefore can approach without a formal introduction, the “seven chances” of the title — and then continuing down an increasingly desperate search. As he runs out of the socially acceptable choices, the options (and the jokes) turn surprisingly transgressive, starting with the gorgeous woman who accosts him in the county club, asking “Would anyone marry me?” with doe-eyed innocence; as Keaton proudly walks her past all the women who rejected him, the girl’s mother shows up to scold her — she’s an underage teen who has dressed up and snuck into the club as an adult. From this narrowly avoided scandal, his choices quickly devolve as random woman after woman is approached and proves to be unsuitable; as a title card explains at the end of this sequence, Keaton approaches and is rejected by “Everything in skirts including a Scotsman.”

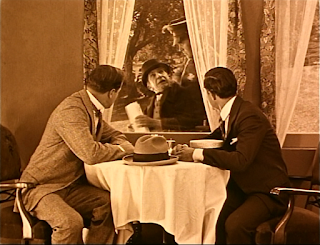

Meanwhile, his partner has secured a church and minister and told Keaton to be there by 5:00, promising to have a backup bride in place in case Keaton strikes out; his bright idea for this is a newspaper ad:

Of course, this leads to the last third of the movie, in which hundreds of women show up; told by the minister that they are all victims of a practical joke, they are out for Keaton’s blood and pursue him through an escalating series of gags, all based on the idea of a mob of angry women cutting a path of destruction through traditionally male groups (drivers on the streets, workers at a job site, a football game) and male authority figures (streetcar operators, a marching police squad). On the one hand, this all reads as an old sexist joke about what unmarried women are like; in contrast to the beautiful country-club women who reject him in the second act, these third-act pursuing brides tend toward the older, less-attractive “battleaxe” stereotype (abetted by the fact that many of them are certainly played by male extras in drag). But, at the same time, the women are shown to be an unstoppable force, literally tossing man after man out of the way; en masse, women have the power and will to upend society itself, working together across generations and even races (more on that below). Along with Dwyer and Dwyer’s mother, who quickly realize that Keaton is just being a ninny and work to patch things up (money or no money), women in this story repeatedly come out ahead.

In addition to Keaton’s expected mechanical stunts there are several surprising and wonderful directorial choices here; later in the film there will be moving vehicles galore, but early on a couple of car trips are handled by Keaton climbing into a parked car, sitting immobile while the surroundings dissolve to the destination, and climbing out. Not only does this economize and focus the storytelling, it hints to the audience that they’ll have to wait for the inevitable vehicular mayhem to come. There’s great use of a moving camera that follows Keaton in his quest, eventually representing the increasingly large mob that’s stalking him. The script also has impressively mature touches, probably from the original source play; as Keaton checks his pockets in the church to make sure he’s got everything, he pulls out a bouquet, the ring, a marriage license, honeymoon tickets to Niagara Falls — and then tickets to Reno, which he puts away in an inside pocket; Reno was the divorce capital of the country at the time, with the shortest residency requirements. There’s no question that Keaton’s character has no illusions about marrying for love.

Reminds me of:

All of those smart, liberated women at the country club have flapper-style bob haircuts, and some of them seem to be specifically channeling Louise Brooks in Pandora’s Box — but a quick check shows that this can’t be the case; Brooks had not yet broken out in 1925. Yet multiple women including the receptionist (“Miss Smith”) and some of the “chances” have the jet-black flapper bob. The ubiquity of short hair is more likely due to Colleen Moore (Flaming Youth was released in 1923) or Olive Thomas (The Flapper and others from the early 1920’s); Clara Bow is also famous for the bob and had appeared on-screen many times by 1925, but her short hair was curly (and Irene Castle, who literally invented the “Castle bob,” also had curly hair). The heroine, Dwyer, has a curly bob too. (Speaking of fashion, I may as well note here the book that Miss Smith is reading; it’s Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks, the trashy (and hugely popular) sex novel of the day, which had been made into a movie just the year before.)So, spoiler alert if you somehow didn’t know — the genius finale that Keaton came up with (and the thing that finally scares off the pursuing mob) is an avalanche of increasingly larger rocks that his character inadvertently sets off. The sequence is hysterical and still amazing to watch; even knowing that those are prop rocks, not really as heavy as they look, their scale to Keaton is startling. I don’t know for sure but I can’t imagine that Spielberg and Lucas weren’t paying homage when they came up with the rock bit for the opening sequence of Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. And yeah, Spielberg’s (single) rock is bigger, but Keaton’s free-fall down a slope with hundreds of rocks is still a more impressive accomplishment overall.

The mass of brides running, running, inexorably running in pursuit — sometimes suddenly joined by another mass from the side, unexpectedly — is certainly reminiscent of a horror-movie situation. Back when zombies were slow, up to and including the George Romero era, this wouldn’t have been as visually obvious. But now that “fast zombies” have arrived, the brides could easily compete as nightmare fuel.

My favorite Charlie Chaplin gag of all time is also a “stone face” bit — in one of his pre-Tramp shorts (The Idle Class), he’s a callous rich man; receiving shocking news in a note, he turns his back to the camera and begins to rack with sobs . . . until he turns and reveals that he’s really just been shaking a cocktail, with no expression on his face at all. I love deadpan.

But then — the guilt!

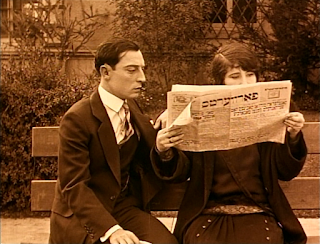

Keaton’s great movies of the 1920s have racist jokes about African-Americans and others, including (as with Dwyer’s servant, here, who is tasked with delivering an important note) actors in blackface. There’s no excusing this now and the blackface isn’t funny, no matter what the intentions were back then. If you are willing to look closely, there’s at least some evidence that Keaton was more progressive than some of his peers (albeit not progressive enough to stay completely away from blackface). There are at least three other roles for African-Americans in the film, one in each section: a well-dressed man at the club who opens a door and steps in front of Keaton just as he’s looking in a mirror; a woman he approaches on the street thinking to propose to her; and one of the many women in the church who accost him when they think they’ve been tricked (in her case she works with a white woman to pummel Keaton); all three of these appear to be played by black actors and not whites in blackface. In a movie from a later time, we wouldn’t think twice about a handful of what are essentially black extras (other than to perhaps note how few there are). But if you compare these four black characters, the only one who is cruelly satirized with the nasty stereotypes is the blackface actor; it’s almost as if the movie is saying that for the joke to be funny, a white guy has to be the buffoon, but when we’re meant to see a black person as real, a black actor will play him. That’s especially the case in the country club scene: It’s odd to see a black person there at all, unless he were to be costumed as wait staff; instead, everyone in the club including the waiters are white, and this gentleman is dressed exactly like Keaton — I’m not sure how that looked in 1925, but watching it today the thought is that this is just another member of the local high society. All this aside — regardless of Keaton’s intentions at the time — it’s still the case that these jokes don’t work today; thinking you’ve “turned black” in a mirror is not a cause for panic, and nor is the idea of wooing or marrying a black woman. There’s a similarly gentle-but-not-funny joke with Keaton approaching a woman who turns out to be Jewish (revealed when her newspaper is in Hebrew).

The music for this 2001 Kino release is by the great Robert Israel, ubiquitous across countless DVD and Blu-Ray releases of classic silents. I like Robert Israel’s music, of course. But . . . as I watched Seven Chances, I started to imagine it with a much more serious, sinister soundtrack, especially during the escalating chase sequence. Keaton’s social failures could take on a far more cynical and sour tone, and the gathering storm of brides could be scored as a horror show; I think the visuals in each case would work perfectly well. In fact the church scene has a lot in common with The Birds: Keaton’s character, unsuspecting, is asleep in the first pew when a single woman drifts into the church and sits at the very back. Then three more women float in; they glare at each other. Then we see a streetcar disgorge twelve women who all arrive in a group. Then from a shot outside the church we see streams of women begin to descend upon the church from every direction . . . .

I should make my whole family and everyone I know watch this every year, yet I never have. I was laughing so hard just while trying to take the screencaps that I was crying.